When natural curves are increased in size, beyond usual ranges, they get the prefix ‘Hyper-’ added

When viewed from the side, the spine should have a gentle inward curve at the lower back, outward curve at the upper back and inward curve at the neck. The inward curves at the lower back and neck are called lordosis, the outward curving upper back is called kyphosis. The lower back is called the lumbar spine, the upper and mid area is the thoracic spine.

There are a number of different reasons an individual may develop an increased prominence in the region between the shoulder blades. The most common causes are Postural weakness, Scheurmanns disease and Osteoporosis.

Postural hyperkyphosis

When standing upright, our spines are under the compressive effect of gravity. If weak in the muscles that hold us up against gravity, we tend to sink in to our spinal curves more, thereby increasing the thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis. Often this slumped posture then involves the shoulders, causing them to round forwards, and the head which pokes forward. A well prescribed exercise program, specifically targeting the common associated restrictions and weaknesses can correct this type of hyperkyphosis to normal alignment. Workstation advice as well as biomechanical training to correct poor movement habits is important in maintaining postural improvements achieved. Both Pilates and the Schroth method have been found to successfully address this presentation. Fortunately our physiotherapists hold dual qualification in both these methods.

Scheuermann’s disease

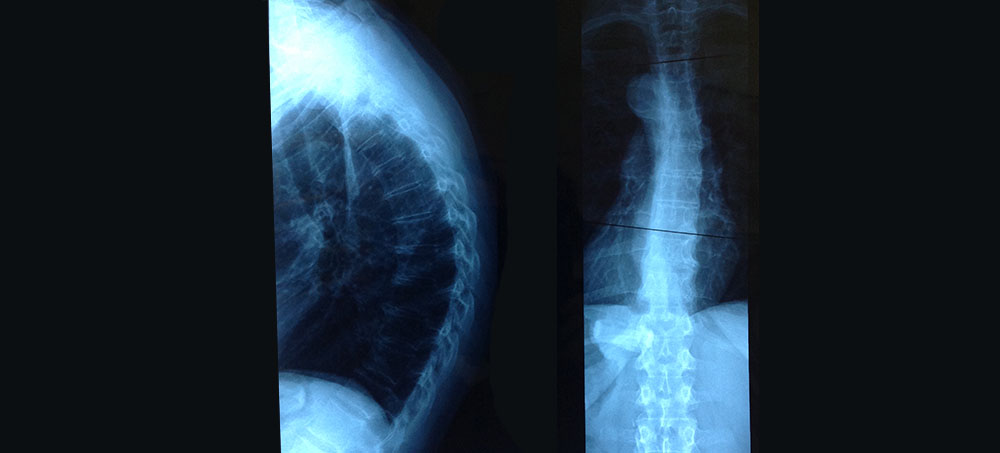

Hyperkyphosis of the thoracic region is usually one of the early signs of Scheuermann’s Disease. Scheuermann’s disease is not something you catch, it is a condition affecting the vertebral growth plates of the spine. It usually presents during the adolescent growth spurt and can lead to the affected vertebrae growing into a slight wedge-shape when viewed on x-ray from the side. We usually can see that the vertebrae in the apex of the curve are shorter in height anteriorly than posteriorly. This then presents as a forward bending or rounding back of this region of the spine. The condition can progress during the growing years and ceases when growth is complete. Classically the affected spine is very stiff, especially into backward bending and twisting. This stiffness is thought to contribute to the development of other anomalies such as Schmorl’s nodes seen on x-ray. Schmorl’s nodes are vertical protrusions of disc material extending into the vertebral endplates and there is debate surrounding them being a possible source of pain.

Unfortunately Scheuermann’s condition is frequently painful and can result in the individual needing to curb activities and sports to keep symptoms to a manageable level. Physiotherapy helps relieve symptoms through direct hands on treatment methods, activity guidance and precise postural conditioning. Postural exercises must address not only local stiffness’s of the involved vertebral segments but also restrictions of the ribcage notoriously found at the front of the chest. This is because the hyperkyphosis at the back results in a closing or collapse at the front of the ribcage. Specifically targeted expansion exercises to the anterior ribcage are essential. Looking beyond the spine and ribcage to the shoulder and pelvis position frequently finds tightness’s and weakness’s also, all that can feed into a forward posture. Comprehensive biomechanical review of all of the movements of daily living, to correct any faulty movement habits that may contribute to the forward curving posture, should be a part of every Scheuermann’s rehabilitation program.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is the most common reason the spine of an elderly person begins to curve forward resulting in hyperkyphosis.

Throughout our life, our bone tissue is constantly replacing, repairing and rebuilding itself. For the first 25 years of our life, our bones become denser due to us building more bone tissue than we breakdown. As they become denser, they become stronger. From approximately 25 – 50 years of age our bone replacing occurs at the same rate. Generally after about 50 years of age, we break down more bone than we make, resulting in a slow loss of our bone density. As the bones become less dense, they become less strong. Once a certain density is reduced to a certain level, the bones are said to be osteoporotic, the individual has osteoporosis.

Weak bones are more likely to sustain a fracture. In the spine, the vertebral bodies are a frequent site of crush fractures that can occur from everyday things. Much of our life involves bending forwards which places increased compressive load through the vertebral bodies. Adding loads such as lifting heavy washing baskets or sneezing and coughing can put high ‘squashing’ forces through the vertebral bodies and if osteoporosis is present, they can be at risk of sustaining a crush fracture. Multiple mini crush fractures are not uncommon and lead to a reduction in height of the front of the vertebral body leading to the person’s spine bending forward.

Postural strengthening is an important part in the management of osteoporosis. Strength in the muscles that endeavour to prevent forward rounding is important to reduce loads on the front of the vertebral bodies and also assist the person to keep upright for ease of functioning. The muscle tensions that pull through the muscle attachments on the bones, together with exercises in weight bearing, have been found to stimulate bone deposition thereby increasing their density.

Exercise programs that aim to improve balance and stability with the goal of reducing the likelihood of falls to decrease the chance of sustaining fractures is paramount.